Connecting to the Desert Landscape

This blog post reflects on artist Moya Radley's transformative experience painting in the Nevada desert in 2023. Faced with intense heat, unfamiliar terrain, and the disorienting challenge of driving and creating in a foreign environment, Moya was pushed well outside her comfort zone. When her travel companion contracted Covid early in the trip, it added further complexity, requiring resilience, adaptability, and emotional strength.

Painting in 40-degree heat, Moya battled the elements, with her pochade frequently toppling into the desert dust, embedding the landscape physically into her work. These difficulties became part of the creative process, resulting in artworks that carry the literal marks of the desert. Influenced by the artworks of Jim Musil, Moya began to truly see and appreciate the subtle, often overlooked beauty of the arid landscape. This experience deepened her connection to the environment and to her own voice as an artist, reminding her that profound creativity often emerges through challenge and discomfort.

In 2023, I was fortunate to embark on a deeply challenging and transformative artistic journey in the Nevada Desert. The experience was unlike any I'd had before — not only because of the raw and unforgiving environment, but also due to the unexpected personal challenges that came with it.

Experiencing the Nevada desert

After spending a day recovering from our 24-hour journey to Las Vegas by exploring suburban parts of Las Vegas and the local Dick Blick's art supply store, my travel companion, Lynn, and I decided to explore further afield. We set out on a long road trip crossing dry country from the northern part of Nevada, travelling close to Kingman in the Arizona desert, drawn by the strange allure of the Joshua Tree Forest. The Mojave and Nevada deserts are places of extremes. The heat was relentless, soaring above 40 degrees Celsius, and the road unfurled through a landscape that at first seemed barren and lifeless. Colours were so muted and foreign — soft greys, light purples, bleached ochres, dusty pinks — that they almost disappeared into the haze. We passed through stretches of native reserves and long, empty miles where the silence pressed in, broken only by the hum of tyres and the occasional dart of a lizard or a bird we didn't recognise.

Yet the deeper we drove, the more the desert revealed itself. Joshua Trees began to appear, scattered like surreal, ancients sculptures across the sand. Strange cacti stood hunched and waiting. There was a quiet, aching beauty beneath it all — subtle and insistent — that I found myself yearning to understand, to hold onto, to express through painting. Somewhere high above the Pacific, on the flight over, I had begun sketching a Joshua Tree from a photograph; its crooked limbs reaching skyward like a question. So, it seemed only fitting that we'd follow them into the desert itself.

We had ventured some 175 kilometres from our home base at the Hoover Dam Lodge, chasing the desert light and the strange silhouettes of Joshua Trees. The heat was unrelenting — heavy, pressing, almost mythic in its intensity.

Eventually, we stopped at a most nondescript spot — a dusty pull-off that looked more like a truck stop than the gateway to anything remarkable. But Google assured us this was the entrance to the Joshua Tree Forest, and who were we to argue? We climbed out of our Colorado into the blistering heat; thankful we'd remembered to bring hats. The heat was so intense it seemed to press in from all directions, swallowing sound and thought. Still, we wandered briefly among the towering Joshua Trees and scrambled over to a rocky outcrop nearby, taking in the surreal beauty of it all. We only lasted about twenty minutes before retreating to the shade of the car, but before we left, we each picked up a small stone — a quiet souvenir. We tucked them into our suitcases, to smuggle home to our studios in New Zealand — a pocket-sized reminder of a vast, wondrous place that had left its mark on both of us.

Driving us through this alien terrain was a salient test of patience and adaptability. Everything felt counterintuitive — the wrong side of the road, unfamiliar off-ramps, strange signage — and I found myself second-guessing even the most basic of my instincts. There was a constant sense of being slightly out of step, out of place. But that disorientation also forced me to pay closer attention, to slow down and notice things I might otherwise have missed — the subtle shifts in the landscape, the rhythm of local traffic, the long pauses between towns.

I was grateful we had opted for the upgrade at the rental lot — the glistening black Colorado waiting in the car lot like a dark beetle. Its size was daunting at first, especially in tight turns or unfamiliar intersections, but out on the open road, with massive trucks thundering past in the heat's shimmer, its weight felt like a kind of reassurance. It carried us steadily through the vastness — a little cocoon of comfort in a place that asked us to stay alert, and to yield to its strangeness.

The full round trip traced close to 350 kilometres and took around four hours — a quiet loop through the raw openness of the Arizona desert. We returned to the cool hush of the Lodge, dust-covered and a little sun-stunned. Soft drinks were ordered, sketchbooks laid out, and we found a corner in the lounge to settle, pencils in hand. We waited there, quietly drawing, anticipation building — for soon, my art coach, Stefan Baumann, would arrive, and we would meet in person for the first time ...

Painting in Nelson Ghost Town

Painting alongside artists I had never met added another layer of uncertainty to an already unfamiliar landscape. I wasn't sure what was expected of me, or how — or if — I would fit into this creative community. The heat, the unknown terrain, and the quiet pressure of the group dynamic made me question my confidence more than once. But in those moments of doubt, something essential began to form: a deeper trust in my own voice, and a quiet resolve to back myself — even when I didn't quite know the rules of the room, or in this instance, the desert!

We set off early in the morning of our first painting day, a slow-moving caravan of cars winding through the desert toward our first destination: Nelson Ghost Town. Despite the early hour, the heat had already risen. That dry, relentless desert warmth seemed to pull the energy straight out of our limbs before we'd even arrived. Nelson, like many ghost towns scattered across the Nevada desert, was ramshackle and weathered; a jumble of corrugated sheds, relics from another time, and sun-faded history. For artists, it was a place brimming with texture and character, which is exactly why Stefan had brought us there.

The moment we arrived we were rounded up and asked to sign indemnity forms. Stefan informed us — in his usual casual tone — that 36 rattlesnakes had been found on the property the day before. Thirty-six. I resolved, very quickly, not to get too close to anything that looked like it might hide a rattler. We'd come well prepared — art supplies (probably too many), easels, sun protection, and nearly four litres of water each. I chose a spot near our Colorado, using her tailgate as a table to set down my extensive supplies. I was drawn to the light hitting the water tank on the edge of the hill. That would do. In the heat, I had little inclination to explore the surrounds for the "perfect" spot. Lynn set up nearby, her view sweeping toward the beautiful desert ranges in the distance.

We were hastened to begin — no time to overthink. Stefan warned us we'd be completing three paintings in quick succession. I was nervous, unsure how to approach the colours, the speed, or the presence of these other artists quietly working around me. The weathered water tank perched on the hill was a structure that seemed to hold both story and stillness. But there was no time for my usual detail or quiet contemplation. I had to move quickly, laying down paint in broad, instinctive gestures, hoping to catch the feeling rather than the facts. The Colorado had reported 39 degrees when we arrived at 7:45 am, and the temperature was no doubt climbing. I was drinking water constantly, trying to stay focused, trying not to overheat.

After about an hour, Stefan called us together again. It was time to move, to pack up, cross the road, and find a new scene. The group complied with quiet efficiency, shuffling through the dust, easels and canvases in hand. On the other side of the road, the land opened out into soft, rolling desert hills, scattered with brush and shadow. Both Lynn and I found new spots and prepared ourselves to begin again.

The sun was unrelenting now — high overhead, merciless and blinding. As we set up for our second painting of the day, it felt like the desert itself was testing our limits. The heat pulsed up from the ground in waves, distorting the horizon, pressing in on our skin, making every movement feel heavier than the last. The air was dry, brittle, and utterly without mercy. I could feel the sweat evaporating faster than it formed, and we were inhaling water at a frightening pace. Each sip felt like survival.

I began to grow genuinely concerned. Between the two of us, we'd packed close to four litres each, but now, under this inferno, it didn't seem like enough. We still had a third painting to complete, but the idea of continuing without enough hydration was beginning to feel foolish. I started mentally preparing for the possibility that we might need to abandon the plan altogether. Stefan hadn't told us that the old shop on the Nelson Ghost Town site — a weathered structure that looked like a film prop — was still functioning. It hadn't even occurred to me that it might hold cold bottles of water behind its antique façade. I was operating under the assumption that once we ran out, that was it.

Still, we pressed on. I selected another scene, one that captured the soft roll of the hills just beyond the cluster of buildings — their shapes gentle against the hardness of the desert. I had just begun to lay down the first loose marks on my panel when the roar of tyres on gravel caught my ear. A massive ute — even by American standards — slowed beside me, and the driver, a man in a trucker cap and mirrored sunglasses, leaned out of the window and motioned for my attention.

I wandered over, still holding my brush, squinting against the light.

"I found a car," he said, in an impossibly broad American accent. "Off the road. Looks real bad. Where can I find a phone?"

What followed was nothing short of a comedy of accents. I tried to direct him to the shop, assuming he could ask for help there. "Go paaak the caa in the caa paaak, and go to the shop," I repeated, slowly and clearly in my combined South African and New Zealand accent.

"Whaaaad?" he replied, completely baffled.

I tried again, altering my cadence, hoping some combination of syllables might land.

"Whaaaaaaaaad?" he questioned again.

Lynn, within earshot, began to lose it — shaking with laughter at this international stand-off in the desert. From her vantage point, I must've looked like I was attempting to cast a spell with vowels alone. I considered for a brief moment whether I should try switching to an American accent — but what would I even do with the Rs?

Eventually, he gave up trying to decode me and announced, "I'll parrrkk the trrruckkk and go to the store," before driving off in a cloud of dust. Success, in a roundabout way. Lynn and I looked at each other and burst into fits of laughter — two foreigners, overheated and dusty, trying to give directions in a land where everything from the weather to the words felt unfamiliar!

But even the humour couldn't mask the rising exhaustion. The heat had deepened — the car had read 39 degrees when we arrived, and that was hours ago. Now, the ground radiated heat with a fury, and our bodies were slowing under its weight. I managed to finish the second painting — fast, intuitive, chasing the light and energy more than the detail — but I could feel the desert beginning to outpace me.

We packed up, and I messaged Stefan to let him know we were done for the day — that we were heading back to the safety of the Lodge. There would be no third painting for the day. We needed shade, lots of cool water, and the soft cushioning of an air-conditioned room.

While we hadn't completed all we set out to do, we had painted two scenes in heat that felt apocalyptic, navigated a snake-riddled ghost town, survived an accidental cross-cultural comedy sketch, and witnessed how quickly the desert could humble even the best of intentions. That was enough for one day out in the desert sun!

Painting a nocturne

When everyone had returned from Nelson ghost town, sun-flushed and dust-covered, the group gathered for a few rounds of critique before dinner. There was a heaviness in the air. Not just the lingering heat, but the fatigue etched into the artists after a long day under the desert sun. Even Stefan, ever-energetic, acknowledged the toll it had taken. After dinner, as we pushed our plates aside and sipped the last of our drinks, Stefan suggested we make the most of the desert's relative cool and head out to do a nocturne painting. It wasn't much cooler, to be honest — the heat still clung to everything — but the idea of painting in the night intrigued me.

Lynn decided to sit this one out. The day had worn her down, and she was beginning to feel unwell. While she retired to rest in her room, I felt a quiet pull to go. This would be my first foray into nocturne painting; and having admired Lynn's beautiful moonlit landscapes for years, I was eager to see what I could discover in the dark.

I set up outside with a view of the Lodge entrance, where the soft glow of overhead lighting cast long shadows across the gravel and gave the scene a painterly stillness. Once again, the trusty tailgate of the Colorado became my studio table, holding an unruly array of brushes, rags, and tubes of paint. But this time, I wasn't fighting the elements — the wind had died down, the light was gentle, and my equipment behaved. The air, though still warm, felt calm and full of potential.

The painting I produced wasn't particularly good — a murky tangle of shapes and half-captured shadows — but I didn't mind. The experience itself was what I came for: the quiet concentration, the mystery of working in near-darkness, and the hush of the desert night. Jean, one of the new friends we'd made on the trip, had joined me, though she chose to paint a different scene. For a while we worked in companionable silence, each absorbed in our little square of the world.

By 10:00 pm, the others had packed up and drifted indoors, and I found myself the last one standing — still hunched over my pochade box, brush in hand, chasing fleeting glimmers of form and light on an 8 x 10 inch panel. The stillness of the desert at night was unlike anything I'd known: a kind of suspended hush, interrupted only by the occasional gust of warm wind or the distant hum of a passing car. It felt alive and watchful, the kind of place that keeps its secrets unless you're quiet enough to listen.

The glow from the Lodge's old neon sign became my only companion, casting a luminous haze across the gravel. I lingered, reluctant to let the moment go. I wished for more time — more nights like this to explore what the desert held after dark, to see what truths might rise in the silence. But eventually, the heat, the long day, and the weight of my own tired limbs convinced me it was time to go. I packed up, slowly, reluctantly, and made my way upstairs for a cold shower and the sweet relief of rest — grateful, still, for everything the desert had shown me.

Painting Lake Mead

Saturday morning arrived quietly, the desert air still holding the cool of night as I readied myself for our early painting session at Lake Mead. Before heading out, I checked in on Lynn. She had seemed tired the night before, but this morning she was clearly unwell. Her voice was low and strained, and though neither of us said it aloud, the dreaded word was hanging between us — Covid. We tiptoed around it, trying not to name it, hoping perhaps that it was just fatigue, just heat, just too many desert days in a row.

Still, a knot of worry had begun to form in my stomach. I made my way down to the Lodge's lobby and quietly asked if they happened to have any Covid tests on hand. The moment I mentioned the word, the staff's eyes widened — alarm flashing across their faces like I'd uttered something far more dangerous. Stefan was nearby. I pulled him aside and whispered that I suspected Lynn might be sick. He nodded, understanding immediately, and said he'd drive to Boulder City to find a test. In the meantime, he instructed me to join the others at the Lodge's outlook and begin painting Lake Mead.

The air was already warming. I joined the other artists, but kept my distance, conscious that I might be carrying something without knowing. The view over the lake was vast and blue and strangely quiet — but my thoughts were elsewhere. After an hour or so, the heat began to climb again. Before venturing off, Stefan suggested we retreat to the shaded edges of the Lodge under its wide eaves, to continue painting after finishing the Lake Mead paintings.

After finishing off the first pass on the Lake Mead painting, I set up under the shade of the Lodge. Out of the corner of my eye, I noted that something darted past — a blur of feathers and speed. A roadrunner! Smaller than I'd imagined, faster than I could track. It dashed across the gravel, straight into a dry planting bed, and emerged a heartbeat later with a lizard flailing in its beak. Then it was off again, sprinting across the blistering tar like it had placed an order and picked it up from the "McLizard" Drive-Thru. I collapsed into laughter. The absurdity and wonder of the moment felt like a perfect counterbalance to the heaviness of the morning.

Not long after, Stefan returned, test in hand. I took it up to Lynn's room, fingers crossed for a negative result. But the second the line appeared and our worst fears were confirmed. It was Covid. Plans shifted instantly. I jumped in the Colorado and drove into Boulder City, hoping against hope that the pharmacy would sell me antivirals without a prescription. No such luck. So it was back to the Lodge to collect Lynn, then straight to the emergency room at Boulder City Hospital. After navigating the American health system, followed by a quiet consultation with a doctor, we finally had what we needed — a prescription.

Back to the pharmacy again, where antivirals were duly handed over, along with several litres of waaddeeer (known as "water" to those of us in the Antipodes), as the cashier called it in that slow, American twang. I hauled the waaddeer into the back of the Colorado, and armed with tissues, antivirals and pain medication, headed back to the Lodge, tired but relieved.

Back at base in Lynn's hotel room, the day turned administrative. We had to determine whether Lynn and I would be able to fly, and if not, whether the Lodge had availability to extend our stay. We were on the phone with the travel agent, trying to work through contingencies, scanning flights and quarantine options, calculating insurance implications. There were conversations at the front desk, forms, phone calls, and uncertainty layered on top of more uncertainty. It was stressful, and yet oddly clarifying. This was one of those moments where friendship takes the front seat, where you realise that showing up for someone — really showing up — sometimes means putting your own plans, and your own comfort, aside.

To be fair, part of me was relieved I didn't have to go back out into the blazing desert for another plein air session. But more than that, I was struck by the importance of care — how necessary it is to be there for someone when they're unwell, especially when you're far from home. Lynn longed for the familiar — for her own bed, her own air, the rhythm of her own life — and I understood that deeply. Together, we gathered all the information we needed to make a sound decision. We believed we had a window — that she'd be well enough to fly on the date we'd originally planned.

That evening, as we weighed the final decision, the television news murmured in the background. The screen lit up with footage of a sudden attack — Israel had been struck from Gaza. War was breaking out. I watched in quiet horror as the reports unfolded. The world, already feeling uncertain, tilted a little further. Everything felt fragile — our travel plans, our health, our footing in the world. This was confirmed by Stefan the following day, when he strongly suggested we head home before any trouble escalated.

After ensuring Lynn had what she needed after our afternoon of Covid administration, I slipped quietly into the end of the group art critique. The atmosphere had shifted. There was a hush — a shared awareness that someone among us was ill, and that the desert, beautiful and brutal as it was, had worn us thin. It was too hot to venture out again, so Stefan suggested we find something in our rooms to paint or draw — a kind of still life exercise in reflection.

I gathered a few items that told a story of our journey: my chair, a wide-brimmed hat, my merino-possum wrap, a face mask, and my passport — the document that had brought me here and, I hoped, would soon take me home again. I set them up in a quiet corner and began to draw the scene with the artist pencils that I had opted to bring on the journey. Each line was a small act of grounding in a day that had pulled us in so many directions.

Later, as the others drifted down to dinner, I stopped by the general store and picked up something for Lynn and me. The heat had eased a little, the sky outside softening to dusk. In the stillness of that desert evening, after a day of uncertainty, caregiving, and quiet courage, I felt the contours of something steady and important — a lesson in resilience, yes, but also in the simple, powerful act of being there for each other when it matters most.

Painting in the Valley of Fire

On the final day of our painting journey, I was grateful to be travelling with Stefan. We'd arranged it earlier, and as the day approached, I felt quietly relieved. Lynn wasn't well enough to join, and truth be told, I wasn't in the mood to make the journey alone through an unfamiliar, sunbaked landscape. Instead, I climbed into the passenger seat of Stefan's impossibly large Dodge RAM — a veritable ship of the desert. Even though our own Colorado had felt indulgent, this was next-level luxury. I couldn't help but feel a little spoiled.

We rolled out through the parched lands near Lake Mead, the windows tightly shut against the creeping heat. Stefan spoke thoughtfully about the dropping water levels — how the rains weren't returning, how concern was growing among Las Vegans. Every time he rolled down the window to pay a park fee, a blast of desert heat surged in like an open oven. The air-conditioning quickly reclaimed the space, but the heat was always waiting, just outside the door.

We followed the contours of Lake Mead, winding our way towards the Valley of Fire. The land shifted as we moved: subtle at first, then suddenly striking. The colours deepened, the rocks began to blush red, and I was reminded of the earth back in the old Transvaal — South Africa's iron-rich soil that gave off the most distinctive scent when it rained. I found myself wondering what the Nevada desert smells like in the rain. Would it be as earthy, as rich, as alive?

Stefan led us to a small oasis tucked into the arid folds of the land. Pools of clear water lay cupped in the rock, ringed by surprising green. As we paused to admire the scene, a group of big horn sheep descended from the hills. They moved gracefully, entirely at home, curious but unbothered by our presence. Wild, elegant creatures — perfectly adapted to this harsh, golden place.

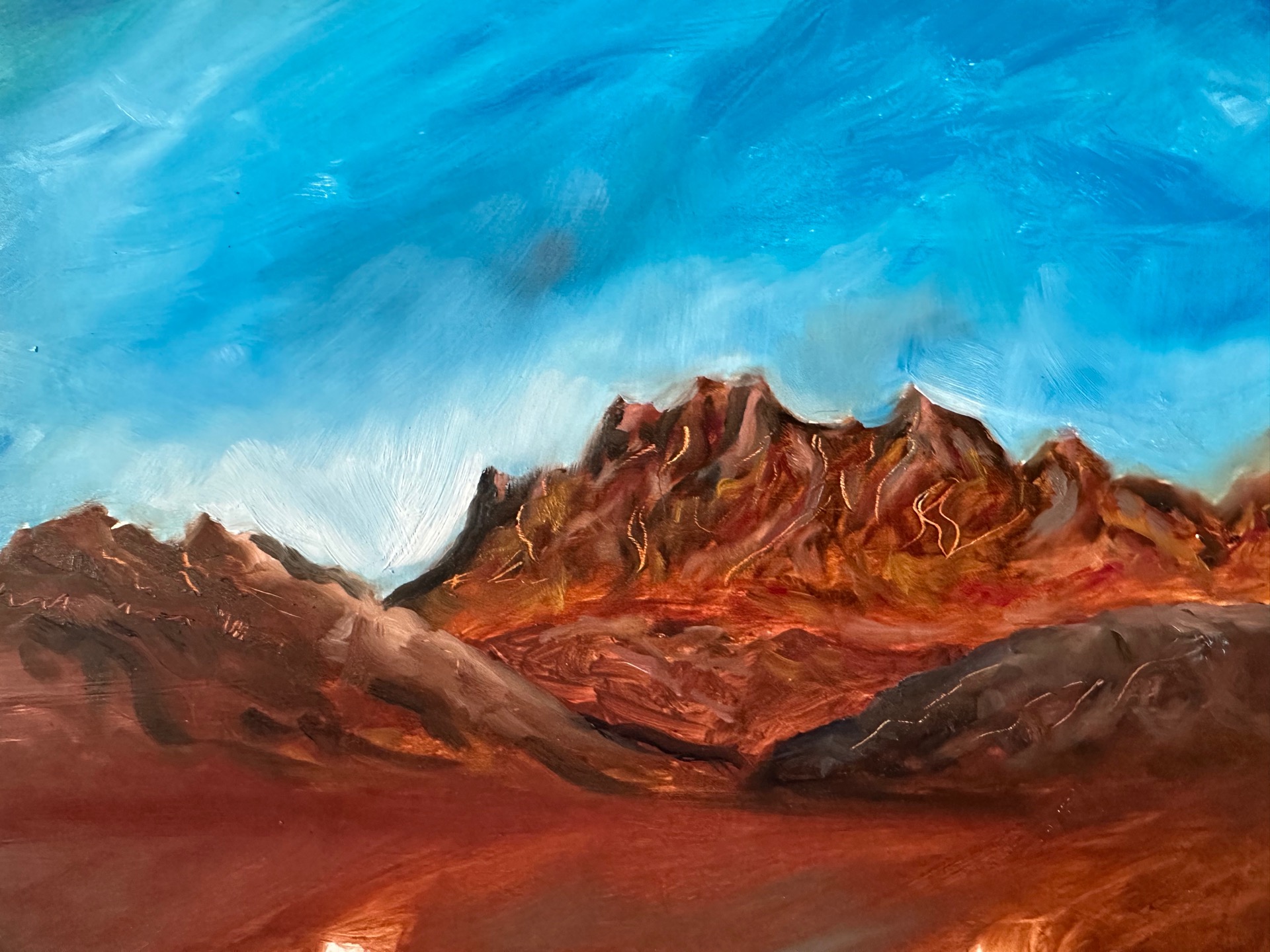

From there, we pressed on into the heart of the Valley of Fire. The land changed dramatically. The colours intensified, settling into every value of burnt sienna, the rock formations rising like ancient sculptures against the startling blue of the sky. It was otherworldly — Mars-like in places— and all around us, the desert shimmered under the weight of the heat.

I muttered something about the temperature, and Stefan, ever thoughtful, found us a patch of shade cast by towering rocks. It was far cooler there than beneath the manmade shelters. I unpacked my paints and found a view I liked: a rugged hill with sparse vegetation, framed in sienna. I began to work quickly. The heat and shifting sun didn't allow for slow contemplation —this was a study born of urgency and instinct, of capturing the moment before it vanished.

Later, as we packed up, Stefan gathered us for a final reflection. He encouraged us to keep pushing — to paint from life, to stretch our abilities, to trust in the challenge. Then we said our goodbyes, and Stefan and I set off again, deeper into the valley, exploring strange, surreal rock formations that seemed plucked from another world. I knew I'd only scratched the surface of this place. I'd love to return one day — there's more painting to be done here, more of the land's secrets to uncover.

By late afternoon we were back at the Hoover Dam Lodge. Lynn was feeling a little better and joined us — still socially distancing — for a cool drink in the lounge. We bid Stefan farewell as he was returning back that evening to his home base at Mount Shasta. Lynn and I, tired of the repetitive fare from the General Store, decided to seek out something more satisfying in Boulder City.

We wandered into the old part of town and found a delightful patchwork of street art, weathered buildings, and small-town charm. It was there that we stumbled across a Cornish pasty shop, and something in me lit up. My mother was of Cornish heritage and had taught me how to make traditional pasties. My grandmother, even more impressively, had mastered the art of the "half-and-half" pasty — one end savoury, the other sweet with apple. A skill my mother never quite cracked, though she tried.

The pasty I had that day tasted just like Mum's. Warm, simple, perfect. We learned that many Cornish immigrants had once come to help build the Hoover Dam — how had I not known that? Over a shared pitcher of root beer and two steaming pasties, we talked about the Valley of Fire, about the trip, about home. Lynn was looking forward to being back in her own space, and I felt a pang of sympathy for all she'd missed.

Still, we'd shared some truly special moments: the quiet wonder of the Joshua Tree Forest, our art-supply pilgrimage to Blicks, laughing our way through the surreal sprawl of Walmart, the glitz of the Las Vegas Strip and the drama of the Bellagio Fountains, painting together in Nelson, and unwinding in the warm-hearted streets of Boulder City.

As we sat there, full and a little sun-weary, I felt grateful. For the landscape, for Lynn's company, for the unexpected quiet beauty of the desert, and for the chance to paint a place that felt so ancient, so alive, and so unlike anywhere I'd ever been.

The desert dust, the stubborn heat, and the occasional chaotic tumble of materials all became part of the creative process. It was a reminder that art is not always pristine or controlled; sometimes it's messy, unpredictable, and shaped by the environment as much as the artist's hand.

My connection to the desert landscape has deepened through the work of Jim Musil, whose evocative descriptions of the desert resonate with my own emerging understanding. His works helped me recognise the desert's profound beauty — one that isn't immediately obvious but reveals itself through patience and connection.

Lessons and reflections

This entire experience was humbling. It reminded me that art is never just about the final painting. It's about the act of engaging — fully and vulnerably — with the world. Painting in the Nevada Desert brought that lesson into sharp relief. It made clear that the artistic process is as much about discomfort, adjustment, observation and resilience as it is about brushstrokes and pigment. What I took from the desert was not just a handful of painted studies, but a deeply felt shift — in how I see, how I create, and how I understand myself as an artist.

Each part of the experience offered a lesson. Sometimes they came quickly, other times slowly, but all were hard-won. What follows are the reflections that continue to shape how I think about painting outside, and about the broader journey of creative practice.

Make your comfort a priority. Painting outdoors demands your full presence, and discomfort caused by heat, cold, sun, bugs, or poor gear pulls you away from the moment. The elements can be punishing, and there is no shame in preparing well for them. That means wearing the right clothes, carrying a hat, applying sunscreen, having enough hydration and food, and knowing where you might find shade. Cold environments require just as much care. When your body is in distress, it is hard — sometimes impossible — to be in dialogue with your surroundings.

Know your equipment as an extension of your body. My pochade box toppled into the desert sand more than once, not because of its design, but because I hadn't taken the time to become fluent in setting it up. Tools should feel like allies, not adversaries. If you're fussing with gear, you're pulled out of flow. It takes time to develop that ease, but it's worth investing in.

Study the landscape, but be ready to learn from it directly. I spent time before the trip poring over photos of the desert, trying to familiarise myself with what I thought I'd encounter. But it wasn't until I was standing in it — light shifting, heat pressing in — that my visual understanding began to rewire itself. The landscape teaches through presence, not pictures.

Don't assume your usual palette will translate. One of the greatest creative challenges I faced was the shock of colour. The earth tones I use at home in New Zealand simply didn't resonate with what I saw in the Nevada light. My brain didn't know what to make of the reds, purples, ochres, and bleached shadows. It took time, and looking closely at how artist Jim Musil interprets this land, for something to click. Even now, the desert palette feels like a language I'm still learning.

Work fast, reflect slow. Our painting days were intense — sometimes rushed, sometimes restless, always dictated by the sun. We moved quickly, trying to capture something before it slipped away. But later, in the stillness, I wrote. I thought. I revisited what I'd done. That post-practice reflection, however short, is vital. It helps you see not only what happened, but why it mattered. It connects the moment to your wider practice, and lets meaning settle in.

Preparation underpins spontaneity. This is a normal practice for Lynn and I. We plan our excursions meticulously. We have checklists, shared routines, and contingency plans. That planning doesn't kill the magic — it makes space for it. Because we're always prepared when we venture out, we can respond flexibly to what the day of painting brings. We aren't derailed by forgotten tools or poor logistics. We are free to focus on the painting.

Expect people. Welcome them, if you can. When you paint outdoors, you become visible. People are curious. They stop. They watch. They ask questions. Sometimes that interrupts the work, but sometimes it deepens it. I now keep postcard-sized prints in my kit, something small I can hand to someone who's genuinely interested in my work and art practice. These become mementos, invitations, even tiny seeds of connection. I also carry business cards, and a notebook too to capture the details of those who want to know more about my art. These brief encounters with transient viewers are part of the practice too.

Be ready to share your work — or not. The first time someone wanted to buy my work on the spot, I hesitated. I didn't want to part with the piece. It felt too personal, too unresolved. I still have it — a marker of a moment I wasn't quite ready to let go. The second time, I was more prepared. Sometimes, letting the work go is also part of its life cycle.

Learn from others. Always. Reading about other artists' plein air experiences, watching how they handle light, gear, or setbacks — these are invaluable. But so is painting together. In group settings, there's camaraderie, but also quiet mentorship. You observe without being taught. You learn by osmosis. That shared creative energy stays with you.

Ask yourself the hard questions. About halfway through the Nevada desert experience, I began asking myself: Why did I come here? What did I think I'd achieve? Why this place? Who are these strangers? What is this unfamiliar landscape and what does it mean? The questions were unsettling — but essential. I didn't have neat answers. Instead, I began listening to talks by Brian Eno, particularly his reflections on the nature of art and its place in human culture. In one talk, he notes how rarely we ask what art is, or why it matters. These questions are difficult, yes — but also foundational. They force us to confront what we're doing and why.

Your studies don't have to be seen to be valid. The works I brought home aren't showpieces. I won't frame them. They're rough, searching, unresolved. But they are mine. They taught me things that no finished piece ever could. In my studio, they sit like quiet companions, not for display, but for remembrance. Each one carries the weight of what it helped me understand.

Art is not a product — it is an act of becoming. I've walked through art shows and seen the same work, again and again. Same artist, same output, same gestures. I don't judge it — but I wonder: where is your edge? Where are you growing? I didn't go to the desert for perfection. I went for growth. And I got it. Messy, exhausting, exhilarating growth. Brian Eno talks about placing yourself in unfamiliar situations — in "scenarios of surprise" — precisely because that's where creativity is born. New places challenge your assumptions. They force you to see, and solve, and stretch.

The desert changed my brushstrokes. Literally. Since returning, I've noticed a looseness in my hand, a freedom in my gestures. Something from the desert stayed with me — not just visually, but physically. The time pressure, the unfamiliar light, the necessity to paint quickly and without overthinking — these have left their imprint on my style. The marks I make today are part-desert. They carry heat and distance and daring.

Problem-solving is an essential artistic skill. This trip required constant problem-solving. How to deal with Lynn's illness. How to handle possible heatstroke and fatigue. How to translate unknown colours. How to pack paintings for travel. How to paint while feeling uncertain. All of it was part of the creative act. Painting is not only aesthetic — it is logistical, emotional, interpersonal. It demands every part of you.

Learning happens when you're uncomfortable. This is the heart of it, really. Growth doesn't happen inside comfort zones. If you want to become a better artist, you have to risk being a worse one first. You have to get lost in strange colours. You have to make paintings that fail. You have to ask questions that don't have tidy answers. The desert was uncomfortable — but it was also illuminating. It taught me to back myself, to trust in the process even when the outcome felt unsure. It also taught me to get right back out there into a place, context and situation I have not yet experienced to continue my art learning journey and development.

To evolve as an artist, you must evolve as a person. What I experienced in the desert wasn't just a shift in technique or approach — it was a shift in self. I became braver. More observant. More willing to sit with ambiguity. And as I grew, so did my work. That's what I take from this experience more than anything else: that creativity thrives not in certainty, but in motion. In seeking. In pushing into the unfamiliar.

I will return to the desert. Not to repeat this experience, but to build on it. This first trip scratched the surface — now I'm ready to go deeper. I'll go back better equipped, more at ease, but still open to being undone. Because the most valuable thing the desert taught me is this:

Art is not about mastery. It's about willingness — to begin, to fail, to ask, to stay curious, to keep learning and to challenge yourself through unfamiliar situations. And when we allow ourselves to be changed by a place, by a moment, by a challenge — that's when we become more. And in becoming more, we become better artists.

I am deeply grateful for the desert, for the questions it asked of me, and the quiet truths it offered in return. Creativity often grows strongest in the soil of challenge. And sometimes, the most profound beauty is found when we are willing to leave the familiar behind, and simply start again.

My Nevada desert plein air core supply list

I thought I'd share an overview of the plein air supplies I use, in case you're considering heading out to paint — whether in a familiar setting or somewhere completely new. I'm not sponsored or affiliated with any of the brands mentioned; these are simply the tools and materials that I've found work well for me and support my painting practice.- Sienna medium pochade box: there's always a fair bit of debate about which plein air setup is "best," but ultimately, it comes down to what works for you. I chose to invest in the Jack Richeson Sienna Medium Pochade Box, along with the matching supply box. The pochade comes with a glass palette and a magnetic paint shelf — features I've found genuinely useful in the field. After taking the time to master the setup, especially how the different components rest securely on the tripod, I've really grown to love it. I've standardised my study panels to 8 x 10 inches, which not only fit neatly in my panel carriers but also pair perfectly with the pochade's dimensions. Admittedly, my box hit the desert floor a few times, it now bears a few scuffs and desert dust in its joints, but I've come to love those marks. They're reminders of the challenges I faced and the lessons I learned out there. One simple but helpful modification: the glass palette is clear, so I painted the underside with a neutral grey. It makes colour mixing much easier, especially in bright outdoor light where subtle shifts in tone can be hard to judge.

- Foam board panels: these are lightweight, and having determined my preferred size being 8 x 10 inches, are easy to transport in my panel carrier. The foam board is acid free and covered in paper. The boards do need have a couple of layers of gesso applied to separate the oil from the paper to prevent the paper from disintegrating in time. These have become my go-to panels for any plein air, even painting locally!

- Williamsburg oil landscape painting set: for those who follow my work, you will know I am a massive fan of Williamsburg paints, along with Michael Harding and Gamblin. The richness of the colours and soft texture really allow your work to vibrate. For plein air, I use the Williamsburg oil landscape painting set, and add on other colours to augment this. The wee set comes with eight 11 ml tubes (so they are light and easy to transport!), and one 37 ml Titaniam White tube. The paints are sufficient to work with, and you can easily mix additional colours from the tubes available in the set. If you are setting out to paint while travelling, this is an option that does not add unnecessary weight to your luggage.

- Raymar wet panel carriers: these are an amazing bit of kit that allow you to transport up to six wet panels. The plus on these for overseas travel is that they are lightweight and really provide protection for the artwork in transit. I had two of these packed in my suitcase with my completed desert landscape studies. The studies arrived home unscathed! The best bit is that you can leave your panels in the carrier while they are drying too.

- Aluminium foil: it might not seem like an obvious addition to your plein air kit, but I always pack a roll of aluminium foil. It's perfect for wrapping up dirty brushes at the end of a session — keeping wet paint contained and preventing it from getting on everything else. The foil also helps protect the bristles during transport, so I can get my brushes home safely without fuss or damage.

References to explore

If you are new to plein air, and want to give it a go, all I can say is: do it! It might be a wee bit scary at first, but you will grow and develop throughout the process. If you are a bit of an old hand at plein air, there is still a lot to learn! There are some wonderful resources to explore, and people who are involved in the plein air movement, who share their knowledge through publications, YouTube channels or podcasts. I've linked some of my favourites for you to explore.

- Stefan Baumann's Ultimate Guide to Plein Air Painting: published in 2023, and contains a wealth of information about how to approach plein air painting ... and painting in general.

- Plein Air Painting in Natural Light: is a wonderful publication by Aimee Erickson. In the book, she provides practical tips and tools to help you to improve your plein air painting.

- Eric Rhoads, Outdoor Painter: the founder of Plein Air Live! in the United States, is a passionate and engaging educator on all things plein air — and art more broadly. His YouTube channel is well worth subscribing to, as he regularly features a range of artists who share their tools, techniques, and insights into their creative process.

- Artist's talk by Brian Eno | History Museum of BiH.

- Brian Eno on the Purpose of Art | Design Indaba.

- The art of Jim Musil, the artist who describes the desert landscape so beautifully.